Institute for Climate and Peace

Interview with Elsa Barron

In your view, how did the COP29 negotiations in Baku address the intersection between climate change and social justice, particularly for vulnerable communities that are disproportionately impacted by the climate crisis?

One of the major ways that the negotiations addressed this intersection was in discussions about climate finance. Countries that have contributed the least to the crisis of climate change, basically the countries that have produced the least greenhouse gas emissions, are also some of the countries that are facing the harshest impacts of climate change and have some of the least financial resources to repair and adapt. This is a massive climate justice concern because the communities who are most impacted– who are facing loss of livelihoods, homes, and even loss of life– actually haven’t created this problem. Further, countries that have profited from this problem are much more well-equipped with the financial resources needed to manage some of its worst impacts.

The justice imperative is to ensure that wealthy nations that have contributed the most to the problems of the climate crisis provide resources to the rest of the world to be able to accomplish three things: 1) mitigate the emissions that they are producing to cut off climate change at its source; 2) adapt to the coming impacts of climate change and make sure that communities are equipped to be resilient in the face of increasing and intensifying disasters; and 3) provide for losses and damages that have been already incurred by communities at the front line of climate change, making sure that there is some form of repair for both economic and non-economic losses and damages. Given that the major ambition of this summit was to pass a new collective quantified goal on climate finance (NCQG), all eyes were focused on this issue during the two-week negotiations in Baku.

Were there any specific outcomes from COP29 that you see as particularly conducive to achieving climate justice, or were there areas where the negotiations fell short in advancing equity and justice for marginalized populations?

Any given COP has negotiations across a range of topics, So while this COP was heavily focused on finance, there were ongoing conversations on a diversity of topics including gender, carbon markets, adaptation, and the global stocktake. Even if these topics did not produce major headlines, there is an important (although frustratingly slow) process of producing small developments along the way. For example, the text on gender has an important recognition, “that climate change impacts on women and men can often differ owing to historical and current gender inequalities and multidimensional factors….” These kinds of acknowledgements are important for setting the foundation to advance future policy.

However, there are major areas where the negotiations fell short of advancing true justice and equity. The final agreement on the NCGQ set a goal of producing $300 billion per year in climate finance contributions. This is three times greater than the previous goal of $100 billion that had been designated for the years 2020 to 2025. However, when analyzed a bit more closely, it is just barely greater than the original amount when it is adjusted for inflation. More importantly, it is less than a third of what experts estimate is actually needed to accomplish the goals set out in the Paris Agreement. This shortfall even led one delegate from Nigeria to take the floor and label this agreement as a joke, which received applause from much of the audience.

Given the increasingly urgent need for a just transition, do you believe the outcomes of COP29 adequately addressed the role of economic justice, particularly the need for developed nations to provide financial support to developing countries for climate adaptation and loss and damage?

There are major gaps between the outcomes of COP29 and the achievement of economic justice and an inclusive just transition. At COP29, many of the most affected countries advocated for a $1 trillion commitment per year in climate finance. The civil society-led Climate Justice Coalition even rallied around a call for $5 trillion per year, making the resulting agreement of $300 billion per year a let down in light of the extensive costs of climate change.

Another issue of economic justice is the provision of this finance in the form of grants and not loans. The majority of climate finance provided today is in the form of loans, representing 69% of finance in 2022. Many of these loans are offered at high interest rates, citing risk. However, that risk is often the exact result of injustice related to climate impacts, colonialism, and economic inequality. These loans continue to extract wealth from the most impacted communities, making it a crucial issue of injustice in the global system. Ensuring that the $300 billion dollar commitment is provided in the form of grants is just the baseline step in working toward economic justice.

What role did peacebuilding or conflict resolution frameworks play in the negotiations at COP29, and how can these frameworks be more effectively integrated into future climate agreements to prevent further displacement or conflict driven by climate impacts?

The COP29 presidency built on the COP28 Declaration on Climate, Relief, Recovery, and Peace, which ICP signed onto in Dubai. This year, they released the Baku Call as a follow-up to the declaration alongside plans for a Baku Hub, which is intended to be a space for implementation of work at the nexus of climate and peace. One of the continued points of advocacy around these topics is ensuring that countries that are doubly affected by conflict and climate impacts are not excluded from receiving support for climate solutions. Instead, because of the overlapping risks, fragile and conflict affected areas should be prioritized in climate responses.

However it is also the case that COP29 was a greenwashing operation for the government of Azerbaijan to cover up their ethnic cleansing of Armenians in Nagorno Karabakh, an atrocity that illuminates a darker side of the government’s narrative that COP29 could be remembered as a “peace COP.” Efforts to use climate and environmental fronts to sanitize Azerbaijan’s international image have been previously documented. While the government wants to present itself as a leader in the climate space, ironically, it is the fossil fuel industry that is bankrolling its human rights abuses.

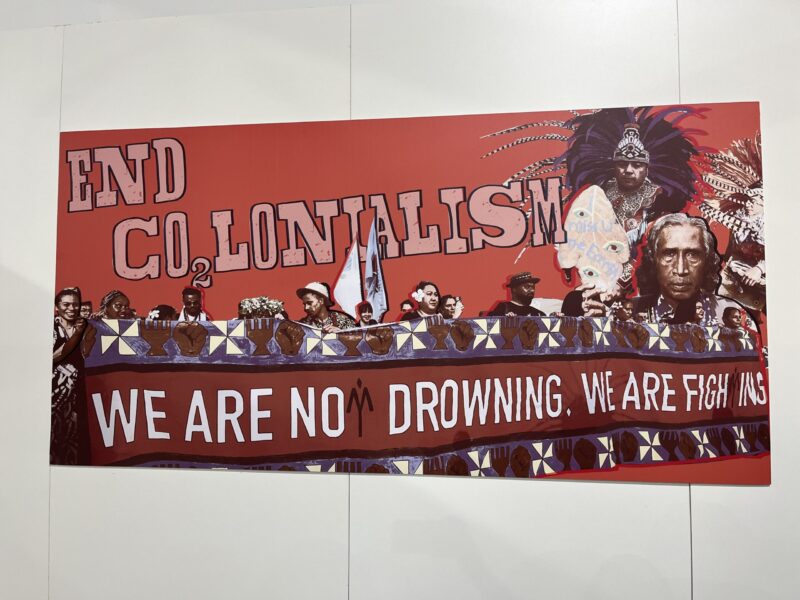

While activism on these topics was hushed in Baku, there were a number of actions in the UN Blue Zone of the conference questioning the intersection between climate change, colonialism, and militarization. These conversations turned solution-oriented when thinking about the pathways through which military spending might be re-allocated into the more ambitious climate finance targets needed to scale up climate action and recovery.

Finally, policy initiatives like the Fossil Fuel Non-Proliferation Treaty apply strategies of weapons nonproliferation policy to the issue of climate change, which similar to war, is having devastating impacts on communities worldwide. This is a promising policy proposal led by nations in the Pacific and an important effort to highlight in the conversation on peace and climate at COP.

Looking forward, what specific steps do you think need to be taken in the next COPs or international climate agreements to ensure that climate action promotes not just environmental sustainability, but also long-term peace and social harmony, especially in conflict-prone regions?

The first action item identified in the Baku Call on Climate Action for Peace, Relief, and Recovery is “to reduce emissions and keep 1.5°C within reach as mitigation along with adaptation and resilience building are the main pillars to avoid further risk by climate change for human security and global stability.” We have to keep this demand front and center, because if we fail to address the emissions causes of climate change worldwide, we will continue to fall back on our efforts toward peace and justice. There is no climate justice without a phase out of fossil fuels, and there is no peace without climate justice.

ICP Delegate Statements

“The discussions emerging from COP29 highlight a profound commitment to amplifying the capacities of local communities to address the challenges they face. By enabling communities to identify issues, understand their unique contexts, and engage in collaborative problem-solving, we foster solutions that are not only relevant but also deeply rooted in their lived experiences. This approach emphasizes the importance of empowering communities to take the lead in shaping their futures, ensuring that the changes they implement are both meaningful and enduring.

This vision of shared responsibility and collective action represents a transformative shift in how global challenges are approached. Instead of relying on external interventions or top-down directives, it prioritizes inclusive consultation and unified effort. By recognizing and respecting the expertise and agency within local contexts, this model strengthens the bonds of trust, promotes innovative solutions, and ensures that the path forward is guided by those most directly impacted.”

–Naima Fifita, Executive Director

“Holding global polluters and wealthy nations accountable for their emissions and ongoing destruction, exploitation, and violence against people and the planet, will continue to be a critical component to achieving climate justice at COP.

The failure to deliver an adequate finance goal at COP29 will once again be at the expense of least developed countries, small island developing states, Indigenous peoples, and frontline communities who have contributed the least to climate change yet bear the weight of its consequences. Ensuring their right to climate reparations and justice is enforced, structural reforms to the COP process must be taken in order to better safeguard the rights of people and nature.

Looking forward, the prioritization of phasing out fossil fuels, radically reducing emissions, decolonizing climate finance, and ensuring just transitions will be crucial next steps. Greater international cooperation and multilateralism at these next COP’s will be imperative to deliver on the Paris Agreement, ensure climate reparations reach those in need, and fortify ambitious climate action.”

–Healani Goo, Associate

“The outcomes of COP29 are a stark reminder of the persistent failure of climate finance to meet the needs of those most affected by the climate crisis. For Pacific nations, whose cultures and livelihoods are deeply embedded with the land and ocean, the stakes are not just environmental, they are existential. These communities, which have contributed the least to global emissions, are facing rising seas, stronger storms, vanishing ecosystems, and devastating economic and cultural losses with little to no recourse. The promised financial support to address loss and damage remains out of reach, leaving communities to confront escalating disasters with inadequate resources.

Despite this disappointment, we must not overlook the transformative power of grassroots and community-led efforts. The resilience of Pacific communities, rooted in Indigenous ways of knowing, offers us a path forward. Indigenous values and practices, that center harmony with nature and collective care, provide invaluable lessons for addressing the climate crisis. Grassroots and community-led efforts across the region are already creating ripples of change. These actions, while local, hold the power to inspire global transformation by demonstrating how collaboration, equity, and sustainability can guide us toward a more just future. COP29 may have failed to deliver, but the strength and ingenuity of our communities show that true leadership is already emerging from the ground up. Lasting change must be rooted in communities, where the impacts of climate action– or inaction– are most deeply felt. If global leaders won’t rise to the occasion, it is clear that communities will continue to lead the way.”

–Jacqueline Akana, Operations Manager