A talk presented by Elsa Barron and Joaquín Paredes Araneda at the COP27 Children and Youth Pavilion.

BY ELSA BARRON AND JOAQUÍN PAREDES ARANEDA

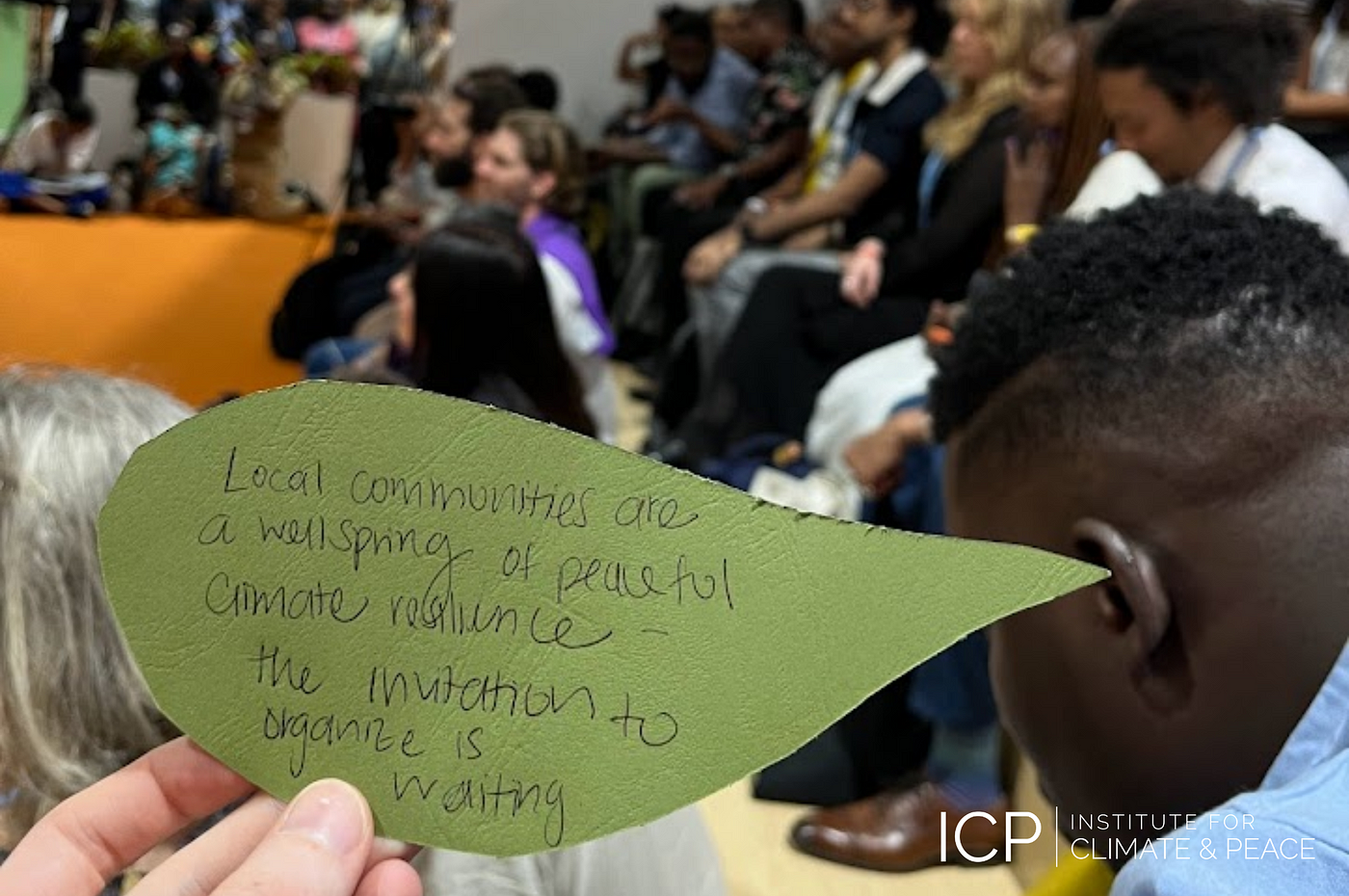

The impacts of climate change increase the risk of violence and disproportionately affect under-resourced communities, making climate change a threat to peace and justice worldwide. However, local responses to climate change provide important opportunities for imaginative world-building. Environmental programs and grassroots initiatives driven by community-rooted youth leadership have proven to be powerful tools for building peace and resilience. This talk at COP27 on 8 November 2022 in the Children and Youth Pavilion (Blue Zone) highlights the active work of youth leaders in environmental peacebuilding around the world, featuring perspectives gathered from a coalition of over 90 youth leaders from over 40 unique countries. This TED-Style Talk was cosponsored by the Institute for Climate and Peace, The Environmental Peacebuilding Association Young Professionals Interest Group, Motum, Peace on Climate, Somali Greenpeace Association, and Re-Imagining New Communities. A transcript is offered below and we encourage you to watch the recording of the Ted Talk here*

Joaquín Paredes Araneda: Hello everyone, my name is Joaquín Paredes Araneda, I’m from Chile and I’m here with my colleague Elsa Barron from the United States. We are going to talk today about youth and environmental peacebuilding. So, Elsa, do you want to take it?

Elsa Barron: Thank you so much Joaquín. So, the first question we’re trying to answer today is: what is environmental peacebuilding? And the reality is that climate change and peace are both global systems that are deeply connected and interwoven. And this means that climate change impacts act as a threat multiplier for forms of violence, conflict, and injustice around the world. This can play out in specific ways including mismanagement or conflict over resources, displacement of communities from their homes, or the exacerbation of existing social, economic, and political instabilities around the world. But there’s a flip slide. In a world impacted by global climate change, peace is equally interconnected and equally important to building opportunities and solutions to address the climate crisis. And, so, this kind of environmental and climate peace must not only be the absence of violence but the presence of just, strong, and equitable communities. And so to take that kind of broad theory of environmental peacebuilding down to the ground, we have three examples: one that touches on family, community, and faith; another that deals with students organizing for action; and the last, engagement for policy and dialogue in peacebuilding solutions.

“…having the people that are most affected by the climate crisis participating in decision-making processes that affect their livelihoods can build healthy responses to climate-related crises and avoid conflict.”

– Joaquín Paredes Araneda, Corporación Motum

So the first [example] is rooted in family, community, and faith. It’s based at Tent of Nations Farm in Palestine. [It is] a family that has been directly impacted by militarization and securitization in attempts to displace them from their land- ranging from actual eviction orders to electricity, water, and road closures by the military, and destruction of their crops including the symbolically peaceful crop of the olive grove. But in response to these challenges and examples of violence, they have responded to electricity cut-offs with solar panels, water cut-offs with rainwater harvesting, and the destruction of their crops and communities by bringing together youth to educate and re-plant together, sustaining their vision of sustainable, creative, environmental non-violence to the opposition that they face.

“Environmental peacebuilding and environmental peacebuilding education are an adaptation solution.”

– Joaquín Paredes Araneda, Corporación Motum

The second example comes from Aotearoa New Zealand, where a group [called the] Student Volunteer Army — which is actually anything but an army in the traditional sense — has come together to mobilize, to build community, to organize, and to equip themselves to respond to climate impacts resiliently and peacefully. In particular, they have been mobilizing to respond to increased flooding and have worked with the Institute for Climate and Peace in capacity building. This community, by prepping themselves for climate resilience and adaptation as a peacebuilding solution, has prevented the militarization that can come in response to disasters when the military is the only equipped institution to respond.

The last example comes from my home community in the United States. Where a group of high school students, under the name Confront the Climate Crisis, has come together to do the much needed — what I would classify as peacebuilding work — to bring together polarized political communities in Indiana, a largely conservative state, to take action, to build legislation, to confront the climate crisis, and to build a task force that works intersectionally to address these challenges.

“The first [takeaway] is for policy-makers and decision-makers to consider the interlinkages between climate change and violence and, on the flipside, climate action and peacebuilding seriously in the policies and action that they develop.”

– Elsa Barron, Institute for Climate and Peace

Hopefully one or more of those examples from very different parts of the world resonates with you and can show a little bit more about what environmental peacebuilding really is and can be as it’s applied. And, with that, I’ll turn it over to Joaquín to talk a little bit more about why this is important and why you should get involved.

Joaquín Paredes Araneda: Okay, so, why is this important, and why you should get involved in this process. So, we believe, based on these examples, environmental peacebuilding and environmental peacebuilding education are an adaptation solution. So we believe that having the people that are most affected by the climate crisis participating in decision-making processes that affect their livelihoods can build healthy responses to climate-related crises and avoid conflict. So, for this, we can have different examples, like in Chile, where we worked training students with climate education and we also teach them peacebuilding tools that can help them in their daily lives. Because peacebuilding is not only the absence of conflict but, as Elsa was saying, is the presence of just and equitable and strong communities. So, because of this, we want to take all this knowledge and also bring it to the international space and sphere.

“The second key takeaway is an invitation for all youth in this space to think about your own communities and an invitation to get involved in peacebuilding and organizing towards climate resilience in your home community.”

– Elsa Barron, Institute for Climate and Peace

In Latin America, for example, we have the Escazú Agreement, which is the original agreement for access to information, public participation, and justice on environmental matters. And this agreement not only brings new transparency ideas for the Latin American countries in improving the public[‘s] participation, which allows them to help their livelihoods, but, also, it protects environmental defenders in the most dangerous region in the world to be a climate activist, which is part of the work that we believe in.

“The final takeaway is to encourage substantive engagement and leadership of youth in spaces where climate and peace decisions are being made.”

– Elsa Barron, Institute for Climate and Peace

So, taking all this into consideration, we want to invite you to include peacebuilding in your work, in your climate work, because it is an adaptation solution. And we also want to call decision makers to think how peacebuilding has an important goal on loss and damage in the most impacted communities, because [by] giving communities capacity-building around peacebuilding and having more resilient resources and tools, they can also live better lives and be more ready for all of the effects of extreme weather events, problems with transboundary water management, and a lot of other elements, as the climate crisis, as Elsa was saying, is a big threat multiplier. So, thank you. I am going to turn it to Elsa for some final remarks.

Elsa Barron: And we only have three key takeaways for you today. The first [takeaway] is for policy-makers and decision-makers to consider the interlinkages between climate change and violence and, on the flipside, climate action and peacebuilding seriously in the policies and action that they develop. The second key takeaway is an invitation for all youth in this space to think about your own communities and an invitation to get involved in peacebuilding and organizing towards climate resilience in your home community. The final takeaway is to encourage substantive engagement and leadership of youth in spaces where climate and peace decisions are being made. As an example, this pavilion itself is doing a great job. So, that is what we will leave you with today in terms of how to move forward, and we thank you for continuing the dialogue with us.

Joaquín Paredes Araneda: Thank you.

. . .

Elsa Barron is an environmental peace and security researcher, writer, and youth activist. She is a Program Analyst at the Institute for Climate and Peace (ICP), and she organizes climate action amongst youth and faith communities. She is the co-chair of the Environmental Peacebuilding Association’s Young Professionals Interest Group and is the host of the podcast, Olive Shoot, which highlights reasons for hope in the midst of the climate crisis through diverse approaches to environmental peacebuilding around the world.

Joaquín Paredes Araneda is a student of International Development at Bennington College and co-founder of Motum, a non-profit headquartered in Chile, dedicated to mobilizing young agents of change to construct a sustainable future working around climate action and peacebuilding. They are an Ashoka Chile Young Changemaker, a member of the foresight commission of the Senate of Chile, and a Voices of the Future Delegate 2021.

A special thanks to Kashish Ali for transcribing this event.

. . .

REFERENCES

COP27 Children and Youth Pavilion, High-Level Climate Champions (2022)

ICP joins COP 27 as a civil society observer in Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt: reflections and highlights from two weeks dedicated to a global climate response, Institute for Climate and Peace (2022)

Motum, Corporación Motum (2021)

Program, Children and Youth Pavilion (2022)

Regional Agreement on Access to Information, Public Participation and Justice in Environmental Matters in Latin America and the Caribbean (Escazú Agreement), United Nations (2018)

The Future of Climate Change, Institute for Climate and Peace (2020)

Photo Credits: Courtesy of the Institute for Climate and Peace, All Rights Reserved.