Reflections on, and a summation of, roundtables to eliminate gender-based violence. This annual event brings together local practitioners and survivors through sharings of lived experience, programs, and advocacy. ICP shares to hoʻolōkahi.

BY KEALOHA FOX AND HEALANI GOO

This year’s 19th Annual HSCADV Conference (Lōkahi: United in Purpose) took place virtually from June 14–16, 2022. In commemoration of Human Rights Day and 16 Days of Activism Against Gender-Based Violence, we share reflections on, and a summation of, roundtables to eliminate gender-based violence in Hawai‘i and the Pacific Region. The Institute for Climate and Peace (ICP) was honored to attend, share, and present during the conference. ICP believes that when resources are stable and relationships are sound, we are poised for peace. This work is especially relevant to the United States, its affiliated territories, jurisdictions in the Pacific, as well as the Asia region, for which climate forecasts demonstrate novel and disproportionate impacts.

Women bear the brunt of violence: environmental, dangerous living conditions, physical instability, food insecurity, and more. And women are also on the frontlines of revolutionary, gender-responsive implementation of solutions. As said by Zainab Salbi, “Women are not just victims; they are survivors and leaders on the community-level backlines of peace and stability.” One step in this direction is the opportunity to come together. When we share information, educate one another, and collaborate, we multiply our impact beyond individual activism toward community transformation.

The Lōkahi Conference and ICP Approach of Hoʻolōkahi

Lōkahi is the ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi term to describe unity, agreement, unison, and harmony. During the Lōkahi conference, Dr. Kealoha Fox joined fellow panelists: Sanoe Ka‘aihue of Women Helping Women Maui, Khara Jabola-Carolus of the Hawai‘i State Commission on the Status of Women (HSCSW), and Angelina Mercado of Hawai‘i State Coalition Against Domestic Violence (HSCADV) in a roundtable discussion on the Future of the Gender-Based Violence Movement in Hawaiʻi. She shared ICP’s values and approach to hoʻolōkahi. Hoʻolōkahi are the traditional Native Hawaiian actions ICP activates to come closer to creating solutions that promote efficiency, resilience, and peace both locally and globally. We generate hoʻolōkahi by focusing on six areas:

- Indigenous values

- Well-being

- Ethical communications

- Culture of commitment

- Meaningful metrics

- A new narrative.

The perpetuation and escalation of violence against women and girls (VAWG) is not only one of the worst forms of discrimination but also remains the most widespread and pervasive human rights violations in the world. “Gender-based violence (GBV) is first and foremost, a violation of human rights and a barrier to a healthy and peaceful planet for all,” says Kealoha Fox. For women and girls in the Pacific, VAWG is among the highest in the world — about twice the global average.

The current state and future-oriented solutions for improving community and system-wide responses to GBV and intimate partner violence (IPV) were explored in this roundtable discussion. Panelists discussed how the COVID-19 pandemic, patriarchal and capitalist societies, colonization, militarism, gender-blind policies, and climate change are some of the factors that are contributing to the prevalence of GBV and IPV in Hawaiʻi.

Alongside the viewpoints of women and community leaders, each panelist’s expertise provided well-rounded dialogue and solutions that include the perspectives from political, health, environmental, and community sectors. Furthermore, intersectional avenues are offered to express the numerous solutions that can be implemented in societal, community, policy, and system-wide sectors to better address GBV and end VAWG.

The COVID-19 Pandemic and Gender-Based Violence

As COVID-19 dramatically increased isolation — one of the main driving factors for domestic violence (DV) to take place — spikes in GBV and IPV have substantially risen. The COVID-19 pandemic has illustrated the connection between GBV and crises. For many, the pandemic shined a light on the overwhelming prevalence of GBV and IPV in their homes, communities, and around the world.

While the pandemic has compelled us to look at other ways of operating our organizations, businesses, services, systems, and lives, it has also amplified the voices and resiliency of survivors. Though, Angelina Mercado states that “we know that that resiliency is also a result of trauma — but how much trauma are we willing to bear in our community and inflict on one another?”

From the individual to systematic level, the pandemic forced an enormous shift in the ways we operate and innovate. Some of these changes were a win for survivors. Sanoe Ka‘aihue explains that for court advocacy, the process became entirely remote. This made it much easier for survivors to get orders of protection for their households and children, and allowed survivors to be present and share their story in a safe space. Kealoha Fox mentions how the Domestic Violence Action Center (DVAC) made their 24/7 hotline text-based which turned out to be a success and made it more accessible for survivors to reach out if they weren’t able to call. Khara Jabola-Carolus explains how “paying for childcare and removing any type of qualifications was huge and it’s a model of the future that we need for survivors because the more responsibilities that a woman — and it tends to be a mother — have, the less privilege and power that she has.” Further stating that although this model has ended, this can hopefully become a long-term consideration.

“We are in an iterative revolving process right now of what is temporary change and what will be long-term lasting change,” says Kealoha Fox. To better improve systems, organizations, and the lives of individuals and their families, far more lasting change needs to come from all sectors in Hawaiʻi. Businesses need to adopt better internal-based policies and top-down measures to protect and support their employees — especially within industries with an overrepresentation of women of color who tend to be underpaid and lack stable benefits. Additionally, mothers, women, and black, Indigenous, people of color (BIPOC) communities have to be engaged and included, along with the availability of disaggregated data that moves beyond bias, to effectively inform policies and programming. Furthermore, a commitment to feminist action in the political space, proliferation of mutual aid, and generating the political will to change things on the ground, are all contributory advances discussed to better serve survivors and effectively address GBV in Hawaiʻi.

Culturally-Responsive Communities

Cultural inclusivity and cultural-responsiveness are significant elements in building a stronger community around GBV. Sanoe Ka‘aihue states that “We need people who represent the community that they are going to serve. We need diversity. We need people who will adopt the responsibility to take cultural context into account. It makes offering safety and support much more effortless and much more likely — it makes conversations easier.”

When looking at the future of the GBV movement in Hawaiʻi, we have to ask how we can collectively address GBV as a community rooted in our culture and values. How can Hawaiʻi bring solidarity to this issue, devoid of shame, guilt, and judgment? And how can we better address GBV together?

Spikes in GBV and IPV have materialized the need to build stronger communities. Oftentimes, it is usually the people in our communities that we go to first. Angelina Mercado describes the importance of having a community-wide response to GBV and IPV similar to how our communities respond to disasters and mass violence, and how it is just as important to begin the healing process.

“Each of us here comes from heritages and peoples of legacy. Our languages, our cultural practices, our spirituality, our values that are passed down from generation to generation, all of that is so culturally intertwined to who we are within our own healthy, positive, resilient identity,” says Kealoha Fox. Describing that not only does our resiliency sometimes come as a result of trauma, but that our resiliency is inherent in our identities, who we are, and who we are supported by. As a community, we can see an end to GBV and IPV, if we meaningfully address it together. This is part of Kealoha’s ongoing work to understand how the social determinants of health affect wāhine across generations in terms of physical health, mental and emotional well-being, partner violence, incarceration, economic well-being, leadership, and civic engagement.

The Climate-GBV Nexus

The impacts of the climate crisis are not gender neutral. Violence against women and girls (VAWG) and climate change are intimately linked. Climate change impacts safety, natural resources, and social cohesion especially in regions as vulnerable as Asia and the Pacific.

When disasters hit, women are impacted the most and occurrences of GBV spike. Kealoha Fox describes how the data is there and it’s been tracked for over 30 years. In 1990, human trafficking increased from 3,000–5,000 annual cases to 12,000–20,000 following an earthquake in Nepal, 70% of mortalities were women in the 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami that hit Indonesia, violence against women increased by 300% following two tropical cyclones impacting Vanuatu in 2011, and in Singapore calls to helplines increased by more than 25% during COVID lockdowns in 2020.

“What does it say about the community that we live in where there is not just violence on the people but also on the actual environment and climate?” says Angelina Mercado. The compounding effects of environmental degradation and climate change coupled with the exacerbation of violence and conflict, are fueling disparities widely felt by women.

Gender-blind climate and environmental policies and frameworks continue to perpetuate and exacerbate the risks of gender-based violence. Indicating the necessity for gender-responsive, feminist perspectives in the ways we operate as a system and community.

Ho‘olōkahi “is our ability to come together and to be more intentional in creating long-term solutions that promote efficiency, resilience, and peace” — not only just for Hawaiʻi or in the Pacific-Asia Region, but also globally, says Kealoha Fox. Further describing how a new narrative can be formed when well-being, a culture of commitment, Indigenous values, meaningful metrics, and ethical communication are being implemented and at the forefront.

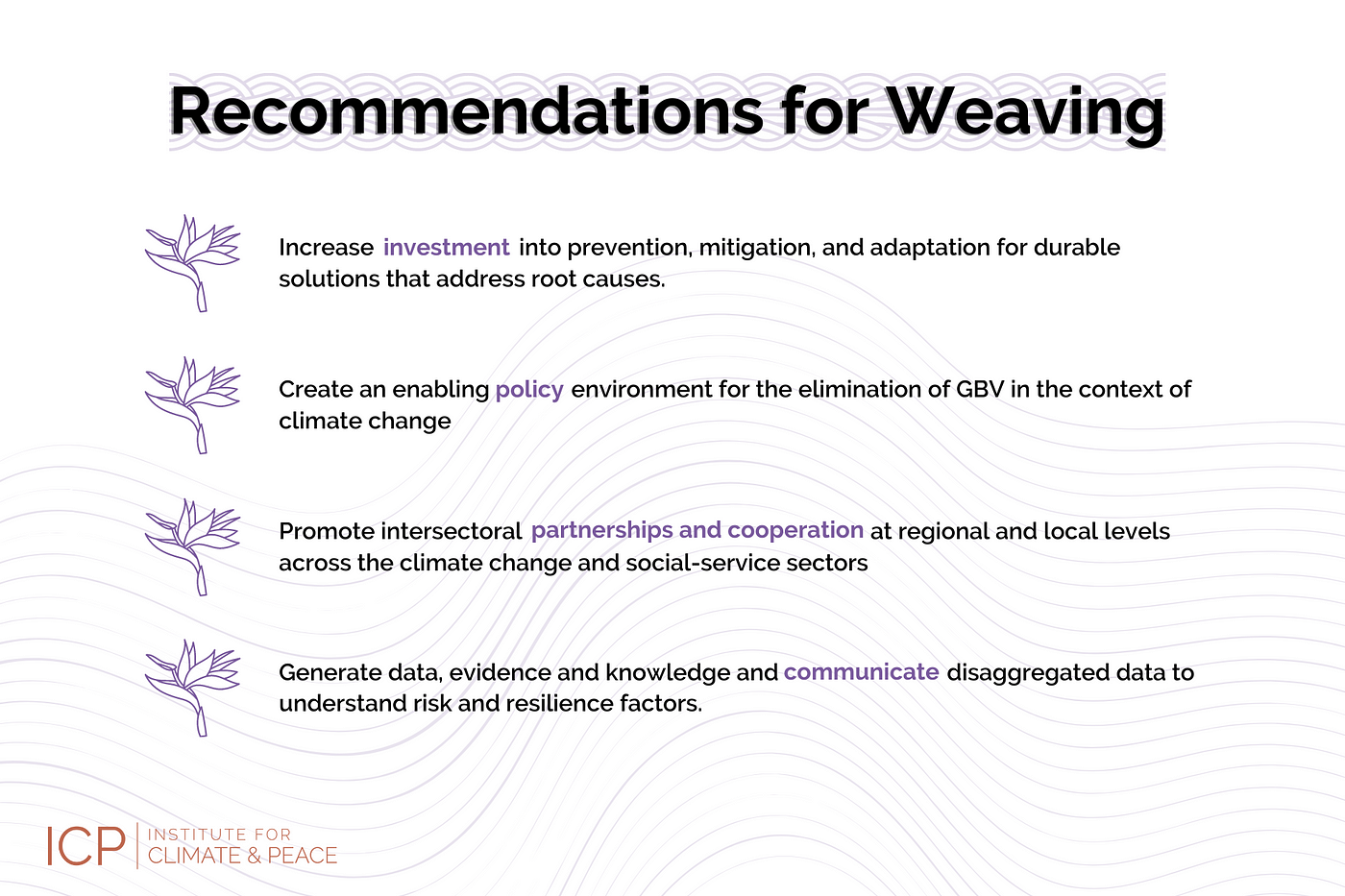

As Hawaiʻi, and the world, grapples with the worsening impacts of climate change, and the disparities that stem from it, it is evident that working intersectionally, and including the dimensions of gender, are imperative in producing effective solutions. “The elimination of violence against women and girls is critical in achieving a sustainable and green planet. GBV must be addressed across the humanitarian, development, peace building and climate change continuum,” says Kealoha Fox. Furthermore, indicating the essential ability to weave together solutions that:

- Increase investment into prevention, mitigation, and adaptation for durable solutions that address root causes.

- Create an enabling policy environment for the elimination of GBV in the context of climate change.

- Promote intersectoral partnerships and cooperation at regional and local levels across the climate change and social-service sectors.

- Generate data, evidence and knowledge and communicate disaggregated data to understand risk and resilience factors.

A New Playbook to End Domestic Violence

The Building Bridges, Not Walking on Backs: A Feminist Economic Recovery Plan for COVID-19, by the Hawai‘i State Commission on the Status of Women, was internationally acclaimed and acknowledged. This recovery plan was created in response to preliminary COVID-19 recommendations from the state-level that excluded any gender-based issues or the mention of gender. Khara Jabola-Carolus says “The Feminist Economic Recovery Plan, I think was initially a sort of intervention, a protest, but it also became a positive vision,” explaining that it deviated from typical gender mainstreaming plans.

Khara Jabola-Carolus explains that Building Bridges, Not Walking on Backs describes how “as long as capitalism exists, IPV will exist.” Stating how the economy we are under is cyclically crisis-ridden, responsible for mass unemployment, homelessness, high-stress environments, human and sex trafficking, and increased DV. Moreover, how militarism is relied on heavily under these systems, and in militarized communities, there are higher levels of IPV because “the military teaches men, predominantly men, how to resolve conflict through violence.” She went on to describe how in a capitalistic society that revolves around profit and wealth accumulation, DV services are therefore not going to be prioritized since they aren’t profit generating, and that “actually healing survivors interrupts accumulating profit.” Additionally, widespread IPV is a result of the conditions of wealth accumulation that keep wages low, keep people overworked and in high states of stress, and isolated, says Khara Jabola-Carolus — further cycling back to public health disparities that plague communities of color and Indigenous communities.

Khara Jabola-Carolus weighs in on what direction we should go to end domestic violence and how we do it. Six actions were shared with during the roundtable:

- Consolidate–Understand the multifactoral root causes of what actually causes DV?

- De-isolate — Lean into the spirit of community engagement and mutual aid. Start at the community level to create communities where isolation does not take place.

- Educate — Start early, often, and long-term. Be specific. We have to talk about it in the framework of gender, how society thinks about women, femme-identifying, men who are devoid of power, and LGBTQ+ community

- Mainstream — Interventions need to be mainstreamed on how to interrupt violence. Every organization needs an internal process, has defined “what is justice” in our organization, and understands that GBV is an obstacle to their success in economic, racial justice, and sovereignty.

- Organize — Invest in paid organizing for DV.

- Energize — How do we excite a base, move people already on our side, or bring in new people on the issue of GBV and IPV?

Future of The Gender-Based Violence Movement in Hawaiʻi

As we think about ways in which we can better serve survivors, advance the GBV movement, and end VAWG, profound shifts need to occur. Shifts in rhetoric and mindset, systematic and policy transformation, justice, increased support for grassroots organizing, and solidarity are some important takeaways discussed for what it will take to achieve this.

“The general public thinks like abusers, not because it’s their fault, but because the institutions that we are raised in are violent, divisive around gender, and promote a lot of sexist myths” says Khara Jabola-Carolus. Similarly, Angelina Mercado mentions shifting rhetoric away from “Why does the victim stay?” to “How do we make the person who is causing harm accountable?” and “How do we then also set up a system to really be supportive as opposed to making them navigate so many hoops and hurdles where the systemic response only further traumatizes them?”

Additionally, the balance and differentiation between tokenism and centering survivors was discussed. On one hand, we have to think about how we honor survivors and uplift their voices without leading them to exploitation. We shouldn’t have to continuously put survivors on display for people to understand or for legislators to do something about it, says Angelina Mercado. Yet, at the same time, “Speaking out and doing activism as a survivor is also part of the healing” says Khara Jabola-Carolus. Further stating that “Pretty much every woman and gender-oppressed person is a survivor of some form of gender-based violence…having to be silent is also very hurtful and harmful.”

The future of this movement means that programs and policies include gender-issues, increased support for survivor organizing, solidarity and openness to have difficult conversations, the ability to work intersectionally, demilitarization and the abolishment of capitalism, building culturally-responsive communities, and a “focus on needs of care, healing, and support for women and gender-oppressed people.”

. . .

Kealoha Fox is the President and Senior Advisor with the Institute for Climate and Peace in Hawai‘i. A graduate of the John A. Burns School of Medicine, Dr. Fox is the recipient of more than 50 awards and distinctions, including being named one of the 20 leaders to follow for the next 20 years in 2022 by Hawaii Business Magazine and a 2022 candidate for the prestigious Pritzker Environmental Genius Award. As a Native Hawaiian woman, Kealoha has been deeply and purposefully trained by esteemed community elders in traditional and ancient Native Hawaiian practices and protocol such as ho‘oponopono, hāhā, and lā‘au lapa‘au.

Healani Goo is an apprentice with the Institute for Climate and Peace and is a recent graduate from the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa with a Bachelor’s Degree in Psychology and a Certificate in Peace and Conflict Studies. As a young Native Hawaiian woman, she aims to continue supporting climate justice and peacebuilding efforts within the Pacific-Asia region. In addition to continuing her studies on the interrelated dimensions of peace, gender, and the environment.

. . .

REFERENCES

Building Bridges, Not Walking on Backs: A Feminist Economic Recovery Plan for COVID-19, Hawaiʻi State Commission on the Status of Women (2020)

Eliminate violence against women, most widespread, pervasive human rights violation, UN Women (2022)

Ending Violence Against Women and Girls, UN Women Asia-Pacific

Future of the Gender-Based Violence Movement Roundtable: Recording, Hawai‘i State Coalition Against Domestic Violence (2022)

Haumea — Transforming the Health of Native Hawaiian Women and Empowering Wāhine Well-Being, Honolulu, HI: Office of Hawaiian Affairs (2018)

Haumea — Transforming the Health of Native Hawaiian Women and Empowering Wāhine Well-Being (Executive Summary and Recommendations), Honolulu, HI: Office of Hawaiian Affairs (2018)

In Focus: 16 Days of Activism Against Gender-Based Violence, UN Women Asia-Pacific (2022)